Elgar’s Broadwood Piano

by Robert Anderson

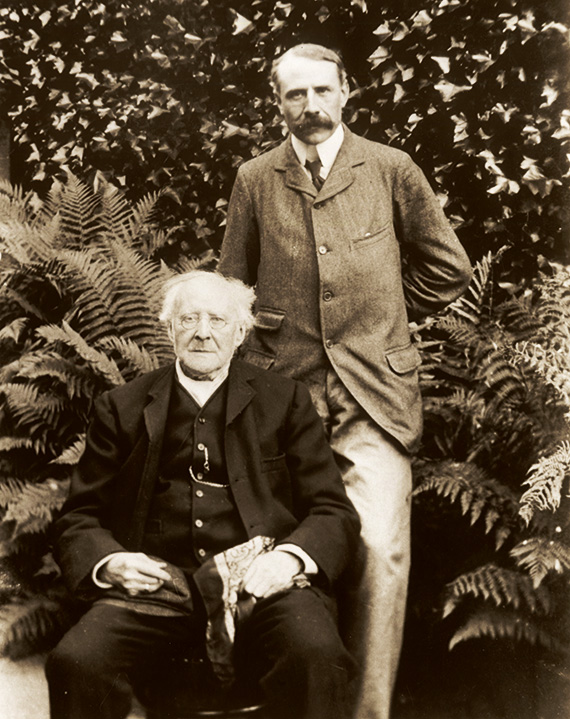

Elgar’s father, William Henry, was apprenticed as a young man to Coventry & Hollier, a firm of London music sellers and publishers, known also as makers of pianos. In 1844, at the age of 19, he was summoned to Worcester as a piano tuner. There he built up a considerable practice, with the dowager Queen Adelaide, widow of William IV, as his most eminent client. Except for a three-year period at the local village of Broadheath, where his son Edward was born on 2 June 1857, William Henry spent the rest of his life in Worcester.

His business prospered sufficiently for him to invite his brother Henry to join him from the beginning of 1860. They were now not only piano tuners, but undertook also to have pianos ‘Removed, Packed, Re-silked, Re-polished and thoroughly Repaired by experienced Workmen’. Three years later they moved ‘to very extensive premises’ at 10 High Street, Worcester, the firm’s final address (the premises are now demolished). They were then advertising pianos by Broadwood, Kirkman (with whom Henry had trained), Collard & Collard, Hopkinson, Oetzmann & Plumb ‘and other esteemed makers, in walnut and rosewood cases in great variety, for Sale or Hire’.

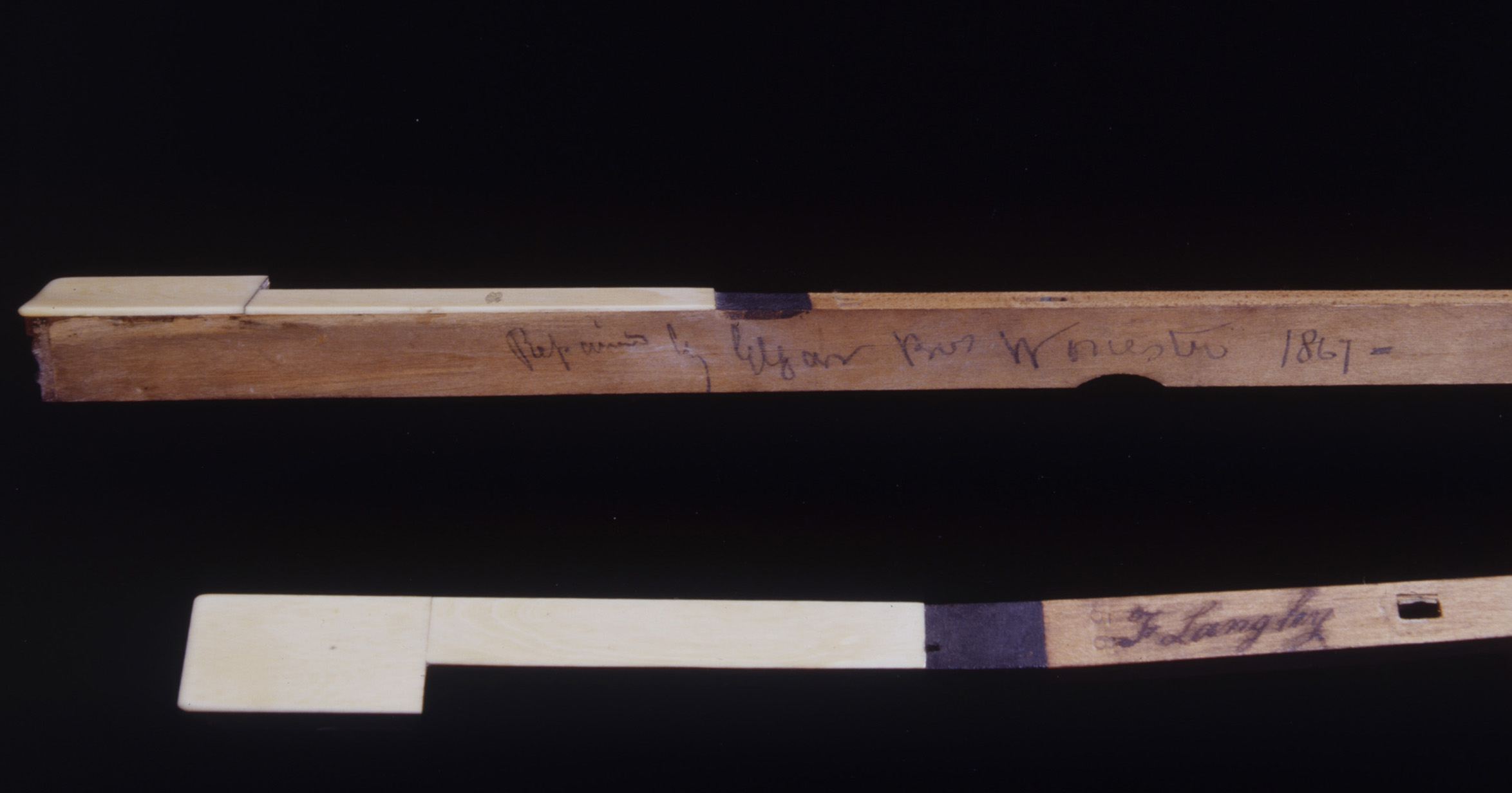

This 1844 Broadwood square piano has a memorandum on the B natural key immediately below middle C; it records the fact that it was ‘Repaired by Elgar Bros Worcester 1867’. How the piano came into the hands of the firm or for whom it was put in order is not yet known. In 1898, however, it springs into vivid life.

Elgar had rented Birchwood Lodge in March of that year from H. Brace Little, the local squire. It was to be a summer retreat from his home in nearby Malvern and a place of constant delight to Elgar. The diary of his wife Alice records many a walk to Birchwood before the cottage was acquired; but that April ‘Dorabella’ of the future ‘Enigma’ Variations came to stay in Malvern and helped ‘find things for Birchwood’. The three of them walked on to Birchwood, and spent a ‘Lovely afternoon’. On 25 April the Elgars went there again ‘to meet Piano’. Mr Little gave them a hand with it, and so a keyboard instrument came to Birchwood.

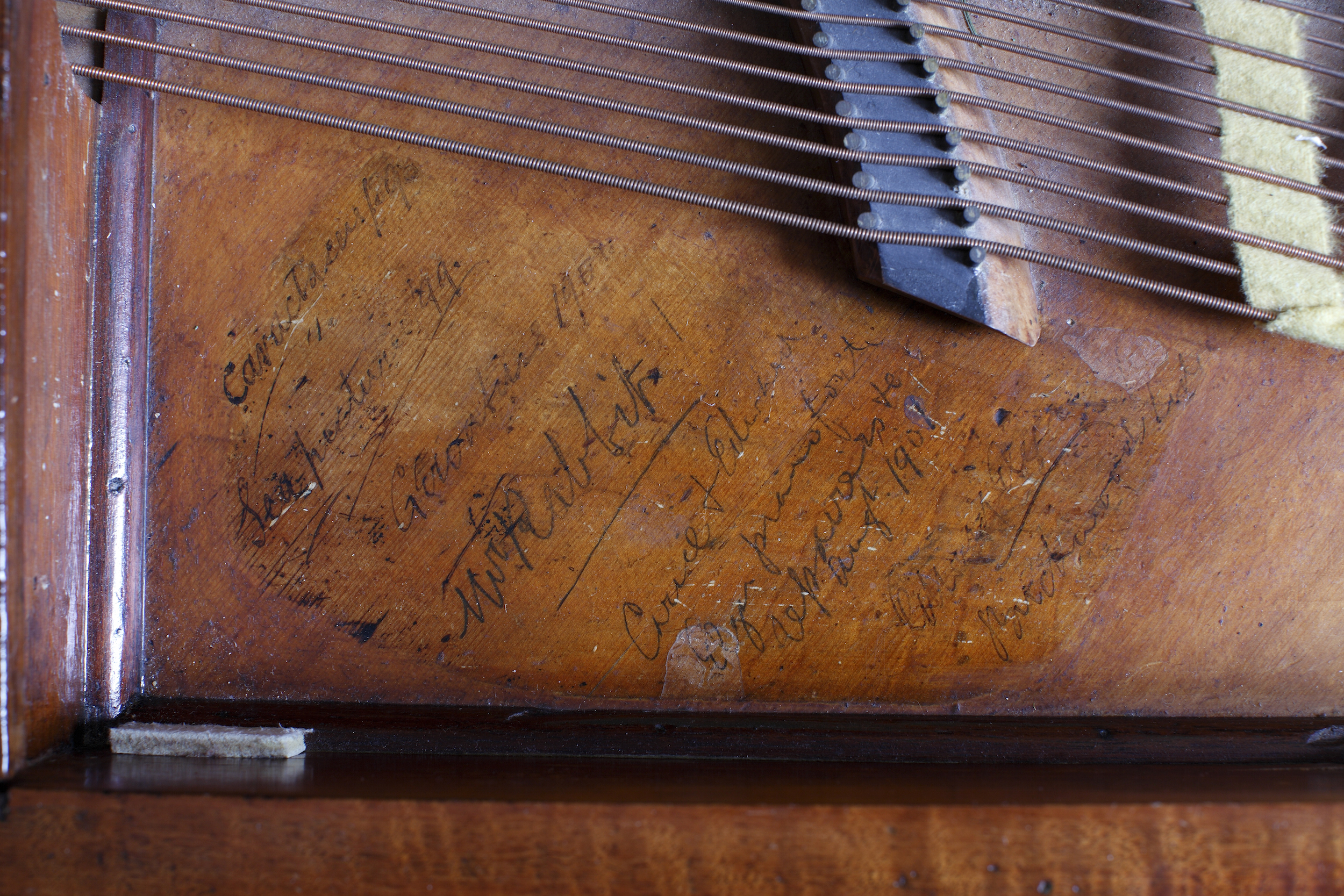

On the soundboard of the Broadwood square Elgar recorded the titles of the works he was mainly busy with at Birchwood. The first was Caractacus, commissioned for the Leeds Festival of 1898 and first given on 5 October. The subject was local, with traditional setting at the Malvern Hills and one scene on the banks of the river Severn. The vocal score was finished by mid-June, but already Birchwood had exerted its influence. Elgar wrote about it to A.J.Jaeger, the future ‘Nimrod’ of the Variations: ‘I’ve been cutting a long path thro’ the dense jungle – like primitive man only with more clothes. But you will see our “woodlands” some day. – I made old Caractacus stop as if broken down on p 168 [of the vocal score] & choke & say “woodlands” again because I’m so madly devoted to my woods’.

‘Dorabella’ described Elgar’s Birchwood study as ‘a tiny place. When a piano, a table, and two chairs were in it there was not more than room to turn round. When they first went up there they had a most comic little old piano. I played a few notes on it and it made a tinny little noise rather like a spinet.’. Though not an impeccable witness, she implies that this was not the Broadwood, but that they soon ‘changed it for a more modern one – and there was even less room in the study.’.

‘Dorabella’ described Elgar’s Birchwood study as ‘a tiny place. When a piano, a table, and two chairs were in it there was not more than room to turn round. When they first went up there they had a most comic little old piano. I played a few notes on it and it made a tinny little noise rather like a spinet.’. Though not an impeccable witness, she implies that this was not the Broadwood, but that they soon ‘changed it for a more modern one – and there was even less room in the study.’.

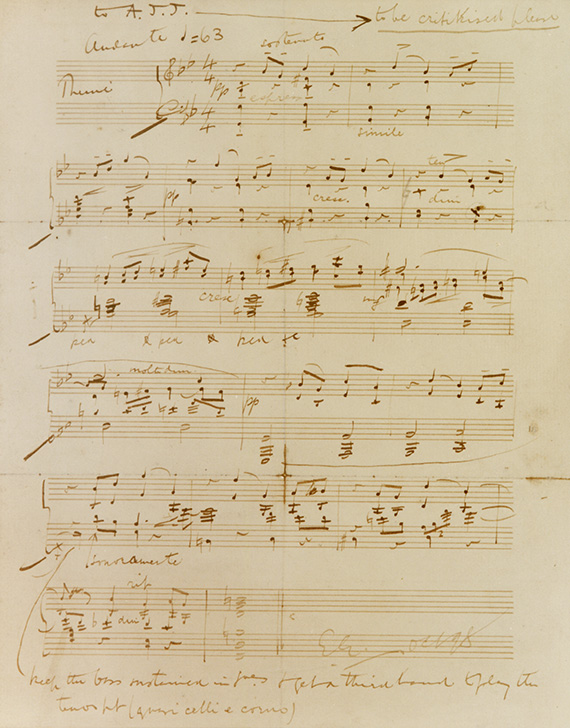

Elgar’s next major work after Caractacus was the ‘Enigma’ Variations, begun as a casual improvisation after a day’s teaching on the evening of 21 October 1898. Some of the characters to be ‘pictured within’, apart from the Elgars themselves and ‘Dorabella’, had already been to Birchwood. ‘R.B.T.’ and ‘B.G.N.’ had walked there with Elgar before the cottage was rented; ‘Troyte’ had taken part in the discussions with Mr. Little; ‘W.N.’ lived nearby at Sherridge and had helped with Caractacus proofs. Elgar omitted the ‘Enigma’ Variations on the Broadwood’s soundboard, because most of the work was written at Malvern. But the Elgars spent some nights at Birchwood a month after Elgar conceived the Variations idea, and it is unthinkable that he would not have tried out material for the work on the square piano. After ‘Enigma’s’ first performance on 19 June 1899 Jaeger urged Elgar to extend the finale. At first reluctant, Elgar ultimately consented, and this very last section of the work, ‘the Jaerodnimgeresque coda’, was scored at Birchwood Lodge in the intervals of ‘Otter hunting’. This may have been the music ‘Dorabella’ heard on 31 July 1899, when she arrived on a very hot day:

I had bicycled from Wolverhampton, forty miles, and arrived, rather warm and dusty, at the cart track leading up through the woods to the house. When I was nearly there I thought I would rest, out of sight, and get cool. I heard the piano in the distance and, not wishing to lose more of it than I need, I soon went on. In a moment I came in sight of the Lady sitting on a fallen tree just below the windows.

Dorabella claimed in her book, Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation (1937) that the music she heard was the opening of The Dream of Gerontius Part II, but for that she was a year out. It was either the tailpiece to the Variations or part of Sea Pictures which Elgar was writing for performance at the Norwich Festival on 5 October 1899. He completed orchestration of the song cycle at Birchwood on 18 August, and duly inscribed its title on the square’s soundboard.

The first half of 1900 was occupied in writing The Dream of Gerontius. Composition in vocal score was complete on 6 June, though at Jaeger’s instigation changes to the latter end of the work were under consideration till the end of the month. With Gerontius orchestration already under way, the Elgars went to Birchwood on 3 July. Two days later Elgar wrote to Jaeger: ‘Well: here we are! There are a lot of young hawks flying about – plovers also – 150 rabbits under the window & the blackbirds eating cherries like mad’. On 11 July he wrote again, quoting the ‘Woodland Interlude’ from Caractacus: ‘This is what I hear all day – the trees are singing my music – or have I sung theirs? I suppose I have’. Under instruction from Mr. Little, Elgar was learning to ride a bicycle in the midst of scoring Gerontius. ‘Dorabella’ came to Birchwood for another couple of nights on 19 July. After the first supper she and Elgar went to the edge of the Birchwood ridge from which they could see the Malvern Hills and the Severn Valley: ‘We sat there a long while that evening and then we went to see the glow-worms. They were a sight!’ On this visit Elgar did indeed play her The Dream of Gerontius:

Then of course the whole scene is wrapped up with the music that I heard, chiefly Gerontius; every available interval was filled with it. After breakfast there was a thunderstorm. I was busy turning over for E.E. and and the storm was getting rather close and I did not like it. I remember how the lightning shone on the music paper, sometimes blue and sometimes pink, and at last a hot white light and a crash of thunder both at once. The noise was too great for piano playing.

Alice Elgar’s diary noted a number of thunderstorms during this Birchwood stay, and Elgar recorded one on the Gerontius full score, in the midst of the Demons’ chorus, where the Angel comments on their nature: ‘It is the restless panting of their Being’. Elgar jotted on his manuscript that the scoring was done at ‘Birchwood Lodge in thunder storm’. Four days after ‘Dorabella’s’ departure, Elgar wrote to Jaeger on 25 July: ‘I don’t like to say a word about these woods for fear you should feel envious but it is godlike in the shade with the snakes & other cool creatures walking about as I write my miserable music’. In a letter to a mutual friend of 3 August Mrs. Elgar commented on their idyllic situation and slightly misquoted the Cardinal Newman poem Elgar had finished setting: ‘We are here in the woods which is very lovely, E. loves orchestrating here in the deep quiet hearing the “sound of summer winds amidst the lofty pines”’. That day the scoring was indeed complete. On the dedication page Elgar wrote ‘A.M.D.G.’ (Ad majorem Dei gloriam), with ‘Birchwood. In Summer, 1900’ below.

The Dream of Gerontius was the last musical work recorded on the soundboard on 3 October of the Broadwood square. The Birmingham performance under Hans Richter on 3 October was unsatisfactory, but at the end of the MS full score were added the signatures of all the orchestral musicians who took part. As supplement to the list Elgar added, in small handwriting, his own initials, those of his wife and daughter Carice, and an enigmatic list of witnesses to the work: ‘Bobbers’, ‘Birra baby’, J W.Fox’, ‘Spiddle’, ‘B Robbit’, ‘Little oddritt’. If these were members of the Birchwood menagerie, favourites of Elgar and his daughter, perhaps they help to explain why ‘Mr Rabbit!’ appears on the piano’s soundboard. Was he one of the ‘150 rabbits under the window’, or maybe an early incarnation of the Peter Rabbit, officially Carice’s pet, who became also Elgar’s ‘confidant’, dedicatee of Owls (strangest of all Elgar’s partsongs), and the notional adapter of certain folksong texts. The Broadwood soundboard gave him the best of company.

Carice herself, about the time of her 11th birthday, brought the inscribed history of the piano full circle. ‘Elgar Bros’ had repaired the instrument in 1867; now ‘Carice & Edward Elgar’ were recorded as ‘pianoforte repairers & Co’ in ‘Augt. 1901’. The nature of the repair is uncertain; perhaps it was necessitated by Elgar’s completion of the first two Pomp and Circumstance Marches at Birchwood on 13 August. Not even Gerontius would have tested the piano more sorely.

The Elgars retained possession of Birchwood Lodge until October 1903; but increasing fame at home and abroad as well as concentrated work on the libretto and music of The Apostles restricted the number of visits there. Alice Elgar’s diary brings their occupancy to an end on 28 October 1903: ‘A. to Birchwood to see things out of house’; and a week later the Broadwood piano was ‘taken away to Stoke’, the home of Elgar’s sister, Pollie Grafton.

Acknowledgements:The late Dr Anderson’s text reproduced by kind permission of the Robert Anderson Trust.

We would also like to thank The Elgar Foundation for allowing access to their archives and for permission to publish the archival photographs in this article.